Site by Nacho

Today’s subject is about staying with the present moment and not letting the past or future come to disturb us. This goes against the grain with ordinary people because it’s understood that we learn from past experience, and need the future as the repository of our hopes and dreams. Currently we live with a certain longing for past times, while entertaining expectations about the future, and this, they say, is the way it must be. But the Buddha is on record as saying that we shouldn’t do that, we shouldn’t long for what’s gone, nor concern ourselves unnecessarily with what might be going to happen, and that remaining fixed in the present is the way to live. But, some say that’s not possible, that they can survive today because they have expectations, regarding, for instance, work, and that they delve into the past in order to learn from previous experience, and although there must be the anxieties connected with such an attitude, yet they’re satisfied with that.

Now, the Buddha had a particular aim: that people to be able to live without any suffering at all, so, how then should they behave when dealing with the past, present, and future? Well, consider a lesson that Buddhists chant regularly called the bhaddekarattagātā, which begins: atītaņnanvāgameyyanappatinkaņkheanāgataņ, and which translates as: ‘one ought not to long for what has passed away, nor be anxious over things that are yet to come’ – in other words one should stay steadily in the present, experiencing the present moment clearly, and attempting to do this increasingly as time goes on. To obey this instruction can and will be troublesome, but, if being, happy, cool and peaceful is what we want, then this is the way we’ll need to live.

Bhaddekaratta – bhadda means ‘auspicious,’ ekaratta means ‘one night.’ In the Pali language when counting days they prefer to use ‘night’ as the measure. We use ‘day,’ as when we say that we’ll be away for three days, but in the language of Buddhism they’d say ‘for three nights.’ Thus ekaratta – ‘one night’ – actually means the whole twenty-four hours. Bhaddekaratta would be a prosperous, or auspicious single night. The bhaddekarattagātā was a particular teaching taught by the Buddha for people who wished to live the ‘noble’ life for just one day, so, if we want to have the very best kind of life for even one day, then this is how we do it. Now, this could be practised for one or for many days, however, here and now we probably won’t be able to achieve one or many days, so we do the best we can, and we practice for some time, for a little while, for an hour, or, perhaps, even for a day - if we could live auspiciously, live the bhadda-life for a day, it would indeed be a praiseworthy achievement.

Think about it, consider: the whole time that we’ve been alive has there been even one day when our life could be said to have been ‘auspicious,’ when we could have called our life ‘bhadda?’ If so then we don’t need to read on, if not, then we do.

The matter we’ll need to understand is time itself, the past, present, and future times. Why is it taught that dwelling in the present, avoiding past and future entanglements is the best way to live? Well, it’s because entertaining the past means that memories, matters from the past will come to disturb, to break up our peace of mind. It will be the same with the future: anyone who entertains unwise expectations, who ‘builds castles in the air’ won’t be able to experience a truly peaceful state of mind. Hopes and expectations are troublesome things. However, at present education systems encourage people to live with expectation, we’re taught to live this way, to live in hope, to build up our expectations, to expect more and more. Life becomes a life lived in hope. But take a look, observe and see how such a life is - is it cool, or is it hot? For so long as we haven’t got the thing we want there’s the feeling of expectancy, and how does that feel? Is that an easy, comfortable experience, or is it disturbing to live in expectation? Some people develop nervous diseases because of this kind of thing, it can torture the mind; not doing as well as we hoped to, as we expected to, can, over a period of time, lead to nervous disease. Hence, if we’re looking forward to getting something then we’re living in hope, so just let that kind of thinking come to a stop and get on with life without allowing expectation to disturb the mind, because when we hope to get anything we’re courting disappointment straight away, whenever we expect to get something or other then we’re prone to disappointment immediately because what we want has yet to arrive, and disappointment, on any level, disturbs the mind, it ‘bites.’ So why hope and get bitten? Don’t bother with hope. When we need something, then we think, and then we stop thinking about it and act, act with energy, with mindfulness, with wisdom. If we act with mindfulness and proper knowledge there’s no biting, if we act with hope and expectation there is. Live on hopes and expectations and they’ll bite; they’ll bite all the time like some predator, like some ferocious animal. Thus, we try to avoid living in hope and instead try to dwell with mindfulness and wisdom remembering to act without letting expectations in to bite us.

Concerning this, the Buddha once took the example of an hen laying and then incubating her eggs. The hen lays the eggs and then she just sits on them; she doesn’t entertain any expectation that the chicks will emerge from the eggs - no hen would be mad enough to do that - she just sits on the eggs; she occasionally scratches and scrapes, occasionally turns the eggs over, and generally does whatever is necessary and right, so that when the time comes the chicks emerge. Be the same, don’t do anything with expectation, allow expectation to arise and it will bite - it will bite and there can be nervous disease, madness, even death. Brooding over what might be going to happen in the future can produce results like that. Thus we need to know how to maintain the mind correctly so that whenever we think then we do it carefully, fully, and correctly, sum up whatever we have to do, and then act with mindfulness and wisdom, saţipaññā, not with hope and expectation. Act in expectation and we act with hunger, and hunger isn’t happiness, it’s suffering. This was taught by the Buddha, but people in the world now don’t teach in this way, they teach children to live in hope and expectation and to get bitten. Hopes and expectations are bound up with disappointment, because if we don’t get what we expect quickly then it means experiencing disappointment. When we begin with expectation there’s bound to be disappointment, and, if we can’t bear with that then we might steal, might do bad things because we haven’t had our expectations fulfilled. Thus, we practise to make the mind normal, we don’t allow the future to come and torture us.

The first section of the Bhaddekarattagātā runs thus: atītaņ nāņvāgameyya: ‘one ought not to long for what has passed away,’ that is, don’t dwell in the past, it’s finished, gone, why bring the dukkha of longing into life. Don’t bring things from the past to torment the mind - if we’ve made a mistake don’t allow it to be a nuisance, stop thinking about it and try to avoid making the same mistake again. Anything of the sort occurring in the future can be dealt with in the same way. Now, concerning the present, how should we act? If we were students, for instance, then we’d study what we need to study without bringing things from the past or future that have no immediate relevance to disturb our cogitations. Thus we could be at ease, comfortable with ourselves. If we allow the past or future to disturb us we won’t feel at ease, we’ll be easily distracted and won’t accomplish as we’d like. This is fundamentally true for everyone; if we haven’t seen this yet then we should, from now on, try to see it. We try not to let thoughts about the past or the future come to torment the mind, instead we do our the best to stay with the present, with whatever’s happening here and now. If we can do this then it’s said that time doesn’t bite us, rather that we turn around and eat time instead.

It says in the Pali that time devours all living things. Time passes, day-time, night-time, and devours, eats all living things, that is, it allows creatures to age and die, to pass away. Time bites us when we hope, when we expect to get something and what we’re hoping for hasn’t arrived yet. Time bites us because we don’t get the thing we want quickly enough. How do we stop time from biting us? Well, we know how time operates so we don’t do anything with expectation, we act with a clear mind, with a smart mind, we act with clarity and don’t allow time to interfere, to have meaning for us. Time has no meaning for us if we avoid thinking too much about past or future events, because then there’s no foolish desire arising towards such things. There can of course be desire for things we’ll need at some future time, but if we don’t think about them unnecessarily there won’t be the sort of unwise desire that causes problems, and when there’s no unwise desire there’s really no time either.

Children will probably know time by the things that indicate it, that tell the time, like a clock, or a day, a night, a month, a year, and so on. These are indicators of the passage of time, things that fix time. These things never bite us because they’re just things that indicate time. But time itself, what is it, where is it? Time? some people say that it doesn’t really exist, but that isn’t true; we don’t agree with that. Time does exist - but for foolish people, for ignorant human beings. If someone is clever enough then it won’t exist for them, but foolish people with their wanting this, wanting that, hoping for this, hoping for that will have to bear the passage of time because of their desiring. Time’s starting point is desire and it continues to exist until we get what we desire - that’s where time ‘is.’ We desire – this is the starting point - then, when we get what we desire, that’s the end-point. Beware of time, it will only have meaning because we have desire. If we don’t desire there won’t be any time, it won’t have a beginning and an end. Thus time exists, but only for ignorant people who have ignorant desires, who have hopes and expectations.

Now, the Dhamma teaches non-desire, that we should avoid foolish wanting, so that anything we do, no matter where or when, should be done without desire as its starting point - then we’ll get what we need to get, but we won’t be bothered by the passage of time, and we won’t have the associated suffering. Then we’ll be above time, above it’s meaning, it won’t exist for us and we’ll experience some degree of mental ease. Those who aren’t bitten by time live their lives above it - desire-less, without the foolish expectations that torment the mind, they become calm, peaceful, attractive human beings. Living that way for even one day would be a praiseworthy achievement.

We’re sorry to have to say that, although we chant the Bhaddekaratta sutta, chant it together regularly, monks, novices and laypeople, we still don’t get the point, and some people, even though they chant this sutta everyday, still entertain doubts about how we, if we don’t take an interest in the past and future, how we can live at all? So pay attention to what the Buddha had to say: he said that if we want to live auspiciously, with an elevated mind for just one day, then this is the way we do it – by not thinking about the past, and by avoiding foolish hope and expectation concerning things that haven’t happened yet. By dwelling in the present moment without the meanings of ‘past’ or ‘future’ coming to disturb us we dwell with a mind that’s peaceful, resolute, strong, which has energy, has the power to do things well here and now, and, what’s better, which is happy and contented, so that, if there’s work for us to do we’ll be able to do it well and contentedly, and if there’s nothing that needs to be done, we’ll do nothing well and contentedly too. This is called bhaddekaratto - having one auspicious night. Supposing someone lives the bhadda-life for one day, then, even if their whole life span should amount to just that one day, their life would have more value than that of someone who had never lived auspiciously, even though they might live for a thousand years. The Buddha taught this way. Now, can we live like this? Because if we live under the power of time it means that we’re enslaved by it, and that we get bitten, get eaten up by it. Longing for the past and hoping for something in the future bites, and then how can we ever be truly happy?

Time exists only for people who desire in ignorance, they experience foolish desire and the meaning of time is immediately ‘born’ for them. If they don’t desire foolishly then time doesn’t exist for them, time isn’t ‘born’ either So, because ordinary people have desires thus they have time too, time exists for them. Hence everybody in this world has to deal with time. When one desires, in the moment that there is desire there will be time; when there isn’t desire, there isn’t time either, time loses it’s meaning. Thus time will exist only when we desire, when we want something in ignorance. So, if we live minus desire, without foolish wanting, then time won’t devour us, rather we’ll do the devouring, we’ll be someone who ‘eats’ time.

The Buddha is recorded as saying that anyone who gets rid of taṇhā, ignorant desire, is someone who eats time. Usually it’s time that devours, devours people, devours all living things, but anyone who puts an end to desire, that one turns around and eats time, which means that time becomes a small matter, something to smile at, an inconsequential matter that can’t eat, can’t bite us. If there’s desire there’ll be time too, and then time will bite. If desire is ended there’s no time, and one turns and eats it, which means one makes time pass away by not giving it meaning, then it’s as if there’s no time, as if we live above it.

We should understand that as soon as time loses its meaning then there isn’t a past or a future, they don’t have meaning either. Thus it’s known as not having time. Devices like clocks, for instance, are devices for fixing time, for telling the time, the seasons of the year, like the yearly rainy season, are devices for fixing the time, and the rising of the sun each day is a device for fixing the time. But time itself is really the interval between ignorant desire and the acquisition of the desired. Therefore, devices for telling the time just tell one, for instance, what time to eat, but for one who doesn’t have desire, who doesn’t have time, like the arahant, they don’t have the same meaning. Days, nights, months, years don’t have the same meaning, clocks don’t have the same meaning, it’s as if they’re given up, relinquished, because arahants aren’t concerned with time in the ordinary sense, or with the problems associated with it. But if it’s a matter of someone needing to work for a living then they’ll still need to be aware of time in the usual way. The more someone is bound to society and the work connected with it, the more timepieces become necessary.

So, we know that there is the passage of time for people who desire in ignorance, clocks are for such people. For people who don’t have the same problem there’s no such dependency, for the desire-less, the passage of days and nights, months and years isn’t a concern. Now, to be without the pressure of passing time, how good would that feel?

Suppose that we did experience a single auspicious day, it would mean that we’d tried to be arahant for that one day. The true arahant doesn’t live the bhadda-life for just one day, however, they do it all of the time, they have a life that’s cool and peaceful, that’s auspicious all of the time. Thus, if anyone wants to be like an arahant for just one day then they do it by living above time, above the meaning of time, above the value of time, by living without desire, without taņhā, craving, without upādāna, clinging, without the defilements, without greed, without anger, without delusion influencing their lives. They dwell above and beyond time.

Suppose that we were always arahant, not just for one day but always, what would we have done to have achieved that? Well, it would mean that we’d given up the present as well as the past and future, that there wouldn’t be a past, a present, or a future for us - because then there wouldn’t be a ‘me,’ there wouldn’t be a ‘me’ to dwell in the present, and when there’s no ‘me’ then there’s no past, present, or future either. Let the ‘me’ go completely and one is arahant full and complete, dwelling above time. But if we’re not yet fully arahant, only bhaddekaratto, then there’ll still be the present remaining, there’ll still be the passage of time, because there’ll still be a ‘me’ to experience it, even so, if while still selfish we dwell in the best possible way then we’ll only have present time to deal with, only the here and now, not the past or the future. The Buddha said that to live for one auspicious night, staying in the present and avoiding the past and future, is something we can do. When we calm the mind then the past and future don’t disturb it and it stays fixed in the present. One then is someone who experiences contentment while still having the ‘self’ delusion. This is known as having one auspicious night. The meaning of time isn’t completely rescinded, in that there’s still the present, but not in such a way that it disturbs.

How many years do we live for, how many tens of years, and yet we never have true peace and happiness. So we try to live one night peacefully by not allowing the past and future to interfere, and by being mindfully aware of whatever we need to think or do in such a way that the feeling of desire doesn’t arise. Ultimately this means acting without the feeling of ‘self’ too, but we still have the feeling of being ‘me’ so we have to stop the past and future from troubling the mind, make them leave the mind alone so that it can do what needs to be done, and then there’s no dukkha. The best present abiding is samādhi, that is, the mind fixed so securely on its object that it stays fixed. Make samādhi, achieve the first jhāna successfully and receive the fruit - vitaka, vicāra, pītī, sukha, ekaggatā. Vitaka and vicāra, applied and sustained thought, pītī, satisfaction, sukha, happiness, and ekaggatā, one-pointedness, are the fruit of samādhi. Ekaggatā, one-pointedness, is the mind alone, focused on one object, free from the meanings of past or future. The mind that’s stilled in samādhi is said to dwell in the present only. Now, if that still feels low then move things up until vitaka/vicāra, applied and sustained thought are gone, which would be the second jhāna, a more intense experience of being in the present; move it up until pītī and sukha, satisfaction and happiness are gone too, until there’s only upekkā, equanimity, and ekaggatā, one-pointedness. Upekkā is the ultimate experience of the present, the purest experience of being in the present minus any suffering or any reaction of the suffering kind whatsoever. The mind dwelling upekkā, equanimous towards all things, dwells only in the present, the past and future cannot come to interfere. Here, upekkā, equanimity can be made to increase until it reaches the ultimate for the still ignorant, the meditative attainment of the arūpājhānas, the formless meditations, which are a yet more equanimous experience, a more refined experience of being in the thorough-going present - which can then be refined more and more until it reaches the highest, the most rarified level where there is no possibility of the past or future arising. At such time the ‘self’ sense is also absent, as with the arahant who, having nothing more to do with clinging, doesn’t have a ‘self’ at all, but for us it’s absent only for the time that we can remain concentrated, when we no longer are then it comes back again.

Being someone who lives the highest way for one day, for half a day, or for one hour may be done in this way - through fixing the mind in the present so that the past and future can’t disturb it, then anything that the mind takes as its object represents the present for it, and, if detachment, equanimity is the object then it will be an extreme example of being in the present. Upekkā, equanimity, has many levels, increasing accordingly as the mind is increasingly samādhi. Mind fixed in upekkā as its only object is ekagattā, one-pointed, and represents the ultimate present, without the defilements of craving and attachment, dwelling above time, dwelling defeating time.

If someone is arahant then the past, present, and future are, for them, completely ceased. If just bhaddekaratta then there’s still the present, but not the past or future. However, if someone were to strive to maintain this bhadda-condition continually it would develop the Dhamma and cut the kilesa, the defilements completely, so that they’d, finally, end up as such. As yet we cannot be so, but we can try to live in the arahant manner; we can try to be like the arahant for just one day. This, then, would be the condition of bhaddekaratto: dwelling in the present - bhaddekaratto: dwelling with an equanimous mind. If someone were arahant then they’d dwell in nibbāna, which is the absolute, the ultimate present.

If it should be asked what the ultimate meaning of the ‘present’ is, then it would have to be ‘nibbāna’ - nibbāna being without any form of concocting doesn’t display the characteristics of arising, persisting, and ceasing, of birth, ageing, and death, thus it has the nature of the eternal present. Having nibbāna as the object of awareness, the arahant lives always in the present moment. Hence, those capable of dwelling in the present can be divided into two groups: the arahants who dwell quite naturally with nibbāna, which is the same as the present, and the not yet arahants who dwell in upekka, equanimity by fixing the mind on an object of concentration.

This isn’t a matter of anyone being damaged or harmed in some way, it’s not because of ignorance or madness that arahants don’t know the past, present, or the future. These people, if they want to, can get involved with time, because they aren’t foolish or subnormal. If, for instance, they want to recall past events in order to learn from them then they can, but in such a manner that it won’t bring them any dukkha. Worldly people when they think about the past, when they recall past matters they make dukkha because they make mistakes, and even though some past event was a happy one it disturbs them, makes them not-peaceful. Someone who’s a bhaddekaratto type is still able to work out some future thing if they should wish to, but in such a way that there wouldn’t be dukkha, because they wouldn’t get caught up in hope and expectation - they’d think about how something should be done, but they’d arrange matters so that only the necessary thinking would happen. Don’t forget that such people avoid hope, avoid the defilements of tanhā, craving, and upādāna, clinging, and, even though they might think, make plans for the future, there’s no dukkha involved because there’s no hope or expectation that could come and bite.

Therefore, we, as ordinary people, can live in the present without the kind of past and future that would be dangerous for the mind. The past then is only a record - memories that we can use whenever we need them, while the future consists in just planning the things that we should do without the sort of hope and expectation that would involve the defilement of desire, of tanhā. For that reason we wouldn’t have enough ignorance for there to be a ‘me,’ or for the mind to take anything as being ‘mine,’ so we could know all things as being ‘just like that.’

‘Just like that’ - tathātā, ‘just like that,’ we’ve mentioned this many times already, but remember it and it will help us to prevent the arising of foolish expectation of the dukkha kind, of the sort of time that bites. Whatever we experience we know it as ‘just like that’ so that we aren’t fooled by it and don’t fall into love, into hate, into anger, into fear, into being led astray in any way. Tathātā will help us to dwell with a normal mind so that the past, present and future cease to be dangerous. Thus, preserve the knowledge of tathātā, keep it well and then we can avoid falling into longing for the past or into harbouring foolish hopes and expectations about the future, we won’t ‘build castles in the air,’ as they say, because we know that whatever we experience is really ‘just like that.’ O

ne who sees anything as ‘just like that’ won’t have foolish desire towards it. If they can see the ‘thusness’ of all things whatsoever then they won’t entertain foolish desire, and when they don’t desire they don’t have time, hence they don’t have the dukkha concerned with time because they don’t have a past or a future in the ordinary sense. This is the seeing of ‘just like that’ that has the most use.

‘Voidness’ is another way of describing the utmost present. There isn’t anything that is more in the present moment than the void mind, because it doesn’t display the usual concocting there’s nothing changeful about voidness. As nibbāna is the ultimate voidness and the void is changeless, then voidness is the ultimate present. If the mind is void it doesn’t give rise to desire and thus doesn’t have the problems associated with time, that is, the past and future don’t disturb it.

Modern education systems don’t teach this kind of thing, they teach in another way, so we don’t get the opportunity to make use of this knowledge. We can have the ability to live above time, but modern education systems don’t teach this, they teach people to rush around, to hurry up, get finished in time, to be quick - so we get nervous diseases all over the place. Worldly education at the present isn’t elevated enough and doesn’t give people the necessary understanding of how to live above the power of time; Buddhist knowledge, however, is elevated enough and does. Present worldly knowledge probably can’t explain time, modern science, because it’s physically based, can’t tell us what time actually is, but Dhamma knowledge can and does: time is the interval between desire and the acquisition of the desired, that, in the Buddhist sense, is time, and for so long as there’s an unfulfilled desire time will have meaning, if there’s no desire then there’s no time, it has no meaning, for time to have a value, to have any power then people need to display foolish desires.

It’s an odd thing that, although we live in the same world, some people live under the power of time and some live above it. Worldly people the world over live under its power, subject to its pressure; the arahant lives above it, above the pressure and biting. Well, we can, if we choose to make the effort, live above time too and for perhaps one day and night we can be bhaddekaratto, we can have the best kind of life for just a short time. Dwelling above time in the same way as the arahant for just one day and night, or even for just one hour, would still be commendable, would certainly be better than nothing.

To get the benefit of experiencing true happiness we need to understand that we can live above the pressure of time by not allowing foolish desire to arise towards anything we experience. By dwelling above the pressure of time we’d be without suffering, and if we could do this continually, then, eventually, time would have no power over us. Or, failing that, if we could be aware enough to practise this some of the time so that it protected us to some degree and allowed us to live to some extent contentedly, then we wouldn’t have to feel too embarrassed when we meet with the cat population, for instance. We’ve said this many times, some will appreciate it some won’t according to their tastes. We ought to feel some degree of embarrassment when considering cats: we suffer from nerves and can’t sleep because time pressures us too much, yet animals, because they don’t desire in the same way, don’t feel pressured by time. Animals don’t have nervous diseases, but people do, so we should feel some shame when we consider cats and dogs, because we don’t see them suffering from the nervous problems associated with time.

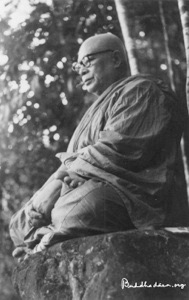

Anyway, it’s hoped that we can take in the meaning of the Buddha’s words on this subject, and that we can live an auspicious, peaceful life by avoiding longing after the past and reaching for the future. Now people don’t seem to understand this, or don’t agree with it, and they criticize - they don’t criticize the Buddha, because they don’t know that this was said by him, rather they understand that it was Buddhadāsa, and so they write criticisms in newspapers, etc. But this piece isn’t about revenge or anything like that, rather it’s meant to reveal that education in this world at this time is insufficient, insufficient in that it fails to reveal that by living outside the power of the past and future we can live at ease without that doing any damage, causing any loss, stopping any development from taking place, without affecting our value as human beings in any way.

So, become familiar with and try to practise this dhamma, this bhaddekaratto, the bhaddekarattagātā that we Buddhists chant together everyday. It’s something we need to do, then, for one day, for one night we could be someone who lives properly, auspiciously, growing in the Dhamma. Practicing to do this for just one day and one night, not all the time, would still mean that we hadn’t wasted a human birth and the opportunity afforded by having met with the Buddha’s teaching.

dhamma vidu.com

The Idappaccayatā Dhamma Discourses

Talk 3.

Living in the Present

31st July, 1982